Migration has been a constant theme in American history and citizens of Albemarle County played their part. Local historical records are filled with residents who eventually moved westward in search of new opportunities. In this article I’ll explore how we can map out where some of those individuals and families ended up, and how their journeys tie into the larger historical picture.

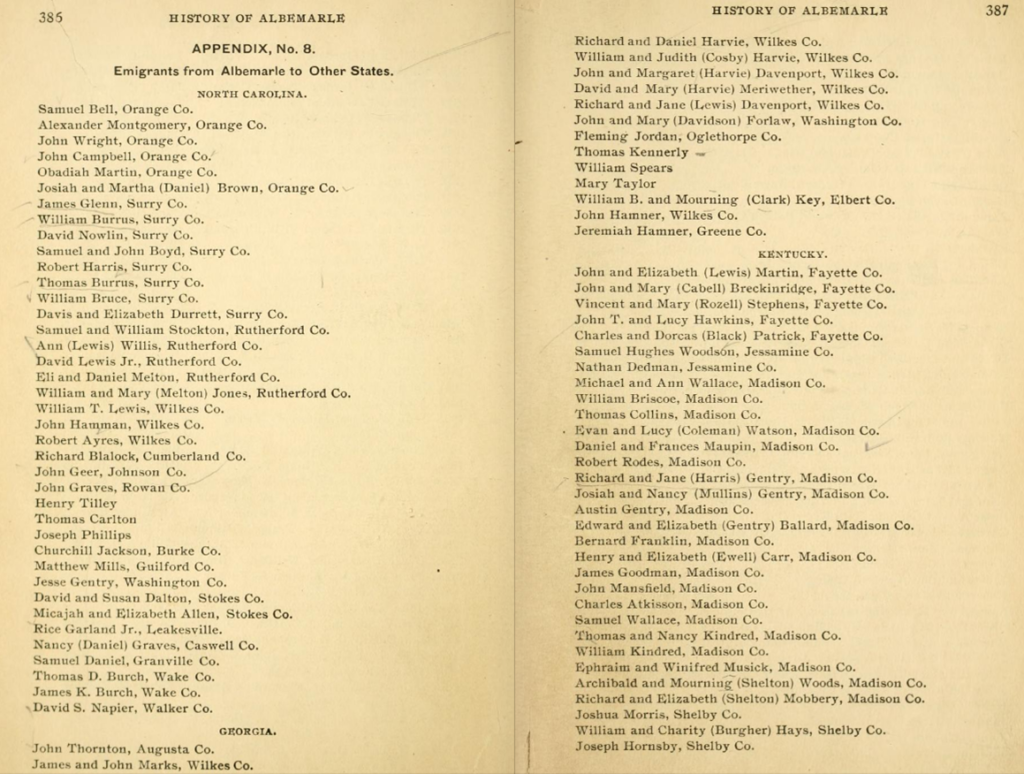

One of my favorite references for Albemarle County history is a 1901 book by Rev. Edgar Woods called “Albemarle County In Virginia” (available from the Internet Archive). His book is packed full of names, places, and interesting anecdotes, making it a good first stop when I’m researching a particular location or topic. Near the back of his book he includes a list of “Emigrants from Albemarle to Other States“, including names and destination locations organized by state.

Earlier in the book, Woods offers this description of early migration away from central Virginia:

“The migratory spirit which characterized the early settlers, was rapidly developed at this period. Removals to other parts of the country had begun some years before the Revolution. The direction taken at first was towards the South. A numerous body of emigrants from Albemarle settled in North Carolina. After the war many emigrated to Georgia, but a far greater number hastened to fix their abodes on the fertile lands of the West, especially the blue grass region of Kentucky.”

Edgar Woods, page 55, Albemarle County In Virginia

He goes on to give this additional detail:

“For a time the practice was prevalent on the part of those expecting to change their domicile, of applying to the County Court for a formal recommendation of character, and certificates were given, declaring them to be honest men and good citizens.”

One great feature of books scanned by the Internet Archive is that they have Optical Character Recognition (OCR) applied, making text in the books searchable and extractable. That meant I could experiment with Woods’ list without having to manually type out all 130+ entries. After a little data cleaning in Excel, and then some GIS magic to associate the counties and states with map coordinates, I was able to map out approximately 100 years of migration outward from Albemarle County. Click a point to see the names of the people who moved to each location:

This data has some important limitations. Obviously, this map is only as good as the underlying list compiled by Woods. It’s certainly not everyone who emigrated from Albemarle County. The quality of the listed destination location also varies. In most cases Woods provides a destination county, but in others he only lists a state. In those instances the map shows a single point representing the center of the state. Unfortunately the list does not include any dates so it’s impossible to do any time-based visualization. Spot checks of people on the list showed a date as early as 1786 and as late as 1887.

My initial reaction when I first saw the destinations mapped out was that the map seemed rather…small. Most of the destinations are concentrated in Kentucky and Tennessee and don’t extend beyond Missouri. However, plotting those locations on top of a map from 1822 (John Melish, from the David Rumsey Map Collection) provides some interesting context:

With this perspective it’s clear that the Albemarle emigrants actually pushed out to the farthest edges of our growing country.

Another visually interesting way to display emigration trends is using “flow lines”, essentially drawing a straight line to connect origin and destination locations. Obviously, the straight line is only an approximation and doesn’t accurately indicate the exact path taken, but it can still provide insight into the overall trend. In the map below, the flow lines are the purple lines connecting Albemarle County (red place marker) with each destination location.

One way to summarize all those individual lines is to calculate something called the linear directional mean. Essentially this takes each line in the dataset and computes a single line that indicates the overall average path and distance of every journey. The linear directional mean is the orange arrow in the map below.

The line runs southwest from Albemarle and ends in Kentucky, not far from the Tennessee border. When I laid all of this on the map, I was fascinated to see that the line runs within 45 miles of the Cumberland Gap (black map pin), a major travel pathway for westward migration through the Appalachian Mountains.

As a side note, the individual credited with “discovering” the Gap and making American settlers aware of it, was Thomas Walker, a prominent citizen in Albemarle County who lived at Castle Hill.

To conclude, this vignette illustrates a few concepts. It shows how thinking spatially can help us explore local history in new ways. Taking a long list of names from a book over 120 years old and putting them on an interactive map makes that history more engaging and helps us formulate additional questions. It can also lead to new insights. In this example we can see how the experiences of those who left Albemarle County tie in the larger story of westward migration that shaped our country.